56 BOUNDING AFTER BEAGLES

BOUNDING AFTER BEAGLES

by David Hancock

“Pour down, like a flood from the hills, brave boys,

“Pour down, like a flood from the hills, brave boys,

On the wings of the wind

The merry beagles fly;

Dull sorrow lags behind:

Ye shrill echoes reply,

Catch each flying sound, and double our joys.”

Those words by William Somerville capture the sheer gaiety of the harehound called the Beagle. But for how long in years to come will ‘the merry beagles fly’ and we go ‘hare-ing after them’? In Robert Leighton’s New Book of the Dog, published in 1912, GS Lowe was writing: “There is nothing to surpass the beauty of the Beagle, either to see him on the flags of his kennel or in unravelling a difficulty on the line of a dodging hare. In neatness he is really the little model of a Foxhound.” He went on to point out that ‘Dorsetshire used to be the great county for Beagles. The downs there were exactly fitted for them, and years ago, when roe-deer were preserved on the large estates, Beagles were used to hunt this small breed of deer.’

Rough-coated Beagles

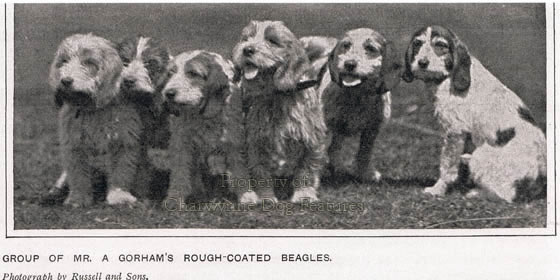

He recalled the Welsh rough-coated Beagle and its look-a-like, the big Essex Beagle, going on to state that ‘A very pretty lot of little rough Beagles were recently shown at Reigate. They were called the Telscome, and exhibited by Mr. A. Gorham.’ He suggested Welsh Hound or even Otterhound blood to get this coat and the increased size of the Welsh and Essex varieties. But from his illustration of Gorham’s hounds, a distinct Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) look can be detected. An interchange of French and English or Welsh hound blood has centuries behind it. Coat texture apart, the Gorham Beagles have the set of ear, ear length and facial expression of the French hounds. Beagle breeders would have known of these 16 inch high Griffons and, to avoid introducing much greater size, would have seen much merit in resorting to the blood of the Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand).

In his Rural Sports of 1801, the Rev WB Daniel wrote: “Beagles, rough or smooth, have their admirers; their tongues are musical, and they go faster than the Southern hounds, but tail much…they require a clever huntsman, for out of eighty couple in the field during a winter’s Sport, he observed not four couple that could be depended on. Of the two sorts he prefers the wire-haired, as having good shoulders, and being well filleted. Smooth-haired Beagles are commonly deep hung, thick lipped, with large nostrils, but often so soft and bad quartered, as to be shoulder-shook and crippled the first season they hunt; crooked legs, like the Bath Turnspit, are frequently seen among them…” ‘Shoulder-shook’ is an old hunting field expression for the jarring caused by badly-placed shoulders and is an apt one. There is no hint of a uniform breed of Beagle in this passage.

Daniel also considered “The North Country Beagle is nimble and vigorous, he pursues the Hare with impetuosity, gives her no time to double, and if the Scent lies high, will easily run down two brace before dinner”; he went on to describe a pocket Beagle, writing: “Of this diminutive and lavish kind the late Colonel Hardy had once a Cry, consisting of ten or eleven couple, which were always carried to and from the field in a large pair of Panniers, slung across a horse; small as they were, they would keep a Hare at all her shifts to escape them…” So we have smooth, rough and wire-coated Beagles, some with crooked legs and some of small terrier size, i.e. pannier-size. There was clearly no attempt to seek a standardized breed, just a competent hare-hound of varying coat texture and shoulder height. The country being hunted often dictated the size of hound, but performance was everything, never appearance alone.

Shoulders and Size

There seems to be an endless debate about shoulder height in Beagles. Writing in Hounds magazine in November 1987, Beagle expert Newton Rycroft gave the view that: “Height alone does not govern pace in beagles. Shoulders and stride are also most important.”, going on to describe how one of the smallest bitches in kennels often performed best in the field because she was the only one with perfect shoulders. He finished his article by stating: “Finally, the 16-17 (inch) beagle. Rightly or wrongly those who breed these get little sympathy from this quarter! If they cannot catch hares with 15 inch beagles then I feel they need not bigger hounds, but better ones.” A reader subsequently wrote in to state that after a mating that produced exceptional quality at 14 inches, a repeat mating produced a litter of five, all over 16 inches. Do you cull quality because of shoulder height? In another issue of the same magazine, ‘Hareless’ was stating “Reduce your size down to 14/15 inch? Well. fine in the lowlands, but too small for a rough moorland country. Quality fifteen inch beagles can soon lose their followers on the right day, but as long as they turn with their hare and retain a god cry do not be put off by the grumblers. It seems illogical to spend ten to fifteen years breeding your hounds to perfection, then start taking notice of people who say they are too good.” I do wish the breeders of show Beagles would take more notice of those who breed the hunting hounds.

Show Flaws and Pack Faults

The differing needs of those who hunt Beagles and those who only show them can lead to the production of two different hounds. Breed type is sometimes over-played by the show fraternity; the requirements of the pack, and purely function can produce plain-headed, lightweight hounds with more ‘hounds general’ than pedigree Beagle in their appearance. This dilemma is hardly new. Writing in the Beagle Club’s Yearbook for 1901, Walter Crofton gave the view: “The fact is, Peterborough, supported by Masters keeping Beagles for hare-hunting and catering only for such, has for some years encouraged the breeding and showing of well-made speedy little hounds and altogether neglected some of the beautiful and typical head points of the Beagle, and with these have gone a few of his working characteristics. On the other hand, the country gentleman and farmer (sometimes for generations) has kept in the family a little ‘cry’ of Beagles for shooting over, has bred to maintain the style of work he admires, and the typical Beagle expression and head, which he loves, but he has often been careless about body parts…” It must be the aim to breed for function without losing the breed. It’s quite possible to ‘lose the breed’ in the packs but more likely in the show ring.

Exhibiting Faults

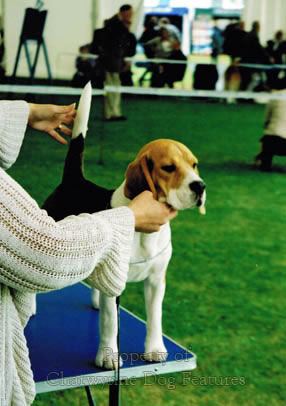

At the final championship show of 2012, the Ladies Kennel Association’s, the Beagle judge was commendably honest in her remarks about the entry. Although the prevalent faults she found are hardly new, it was of value to persist in drawing attention to them. Flat and splayed feet are a handicap to a running hound, the breed standard requires them to be ‘tight and firm’. The commonest cause of such a flaw is a lack of hard exercise; hounds of any breed put before a judge should be in the very best condition. Tails curling over the back, spitz-fashion, spoil an otherwise sound exhibit and this judge was right to resent it. But it has been a long-standing fault in this breed – I can remember seeing it 50 years ago. Show breeders have habitually blamed the packs for this, but I see few signs of it there. The first show Beagle I ever saw, in the 1950s, was an outstanding hound, Ch Barvae Paigan and he came from the pack bloodlines. I was also impressed by a very sound show dog, Glenivy Intrepid, a decade or so ago, really looking like a hare-hound. In recent years, from the ringside, I have been impressed by Ch Nedlaw Barbarian, a wonderfully symmetrical little hound. But show Beagles have, for me, too heavy a body, their legs are too hefty and their feet too large for my liking; the latter may not be helped by a breed standard that specifies feet that are ‘well knuckled-up’ and ‘not hare-footed’. This may be rooted in the distant past when such standards were first written. The Foxhound breeders have moved on; let’s hope we don’t have a ‘mini-shorthorn tendency’ in this fine breed. It was depressing to read the critique of the Beagle judge at the Scottish Beagle Club’s show in April 2008: “Front movement coming on was as bad as I can ever remember, many hounds had large open feet, far too many had short ribcages and long loins…” Did the exhibitors of such hounds truly not know what made a sound Beagle?

Hunting a Pack

Ever since reading Roger Free's Beagle and Terrier of 1946, as a fourteen year old, hunting with a small pack of assorted dogs, has appealed to me. He wrote in times when individual freedom had greater respect but a future need for vermin-control could see his style of operating in the field on the way back and to a greater degree. Free kept and hunted a small mixed pack of 14" Beagles and Terriers for hunting rabbits for the gun. 'Dalesman' described Free's pack as one "which any huntsman might be proud, because they have all those attributes which go towards excellence. Some of these are bred in the hounds -- courage, stamina, nose and tongue -- but the rest must be taught and instilled with patience and knowledge of hounds and their work." But what a challenging self-set task for any ambitious sportsman. Free, not surprisingly, considered that more pleasure was to be derived from hunting your own hounds than from being a follower of a pack hunted by another.

Pack Instincts

Free argued that whereas gundogs are taught by man, scenthounds frequently learn to hunt without the assistance of man and are therefore more self-reliant. He wasn't decrying the merits of gundogs but stressing the need for a different approach to the training of hounds. He advocated choosing a dog that was not afraid to look you in the eye. He preferred to guide a dog rather than 'break' it. He looked for boldness, perseverance, eagerness and biddability. He emphasised the latter and was aware of the menace of self-hunting hounds, oblivious to all recall.

Free concentrated on hunting the hounds and did not himself carry a gun. He normally used four or five couples of Beagles with two or three terriers, finding the latter better in really difficult cover. This meant handling a dozen dogs singlehanded, a testing task. Some sportsmen find controlling one gundog quite beyond them! Generally speaking, terriers and scenthounds demand far more skill in their training than gundogs, partly because of their different instincts and partly because they are often expected to operate in the field as a pack Gundogs have been bred for centuries to respond to human direction in the field; terriers and scenthounds have striven for several centuries to defy all human instructions.

In the United States, the American Rabbit Hound Association registers rabbit hounds bred to meet its standards. Founded in 1986, with 140 clubs in over 28 states, the ARHA promotes hunting competitions and offers a programme of organised rabbit hound hunts. There are six types of hunt competitions: gundog brace, gundog pack, big pack, little pack, progressive pack and Basset. The objective of these field events is to identify those hounds with the best ability to search (i.e. locate the rabbit), flush and drive the rabbit back to the hunter. At the end of each hunt competition, there is a conformation show to try to identify the best-constructed hounds. A comparable parent body here might concentrate the minds of rabbit-hunters.

Value of Rabbit Control

In Australia they have an even bigger problem with rabbit-damage than we do here. Yet, despite developing their own heeler and terrier, they too have never produced a specialist rabbit hound by name. This may be because the breeds taken there from Britain were deemed adequate for the task. In his informative book Australian Barkers and Biters of 1914, Robert Kaleski paid tribute to the Beagle, writing: "Of late years another job has arisen for the Beagle in Australia, and he, like all good Australians, has risen to the job. This job is a very important one. Every grazier knows that after his country has been absolutely swept bare of the grey curse there is invariably one here and one there overlooked in some inaccessible places which pop up and start breeding again. Ordinary dogs do not bother with odd ones like these in bad places; but the Beagle, with whom chasing rabbits is an age-old instinct, goes after these 'last rabbits' with joy and never leaves them alone until run down and secured."

It is this sheer persistence, massive enthusiasm and scenting prowess which makes the Beagle such a superlative hunter - and a handful sometimes for a novice Beagle owner not versed in their avid trailing instincts whenever strong scent is encountered! These instincts are being perpetuated by the working section of the Beagle Club and I applaud their efforts in these difficult days for sporting breeds. The best Beagles that I see come from the Dummer pack, they always look capable of providing a great day’s sport and appearing far racier and more workmanlike, yet still handsome, than those in the KC show rings. The show exhibits for me possess too much bone, walk too stiffly and are often heavy-headed. A recent Crufts critique stated that the most prevalent fault in the entry was wide fronts and what was termed ‘flapping feet’; short steep upper arms were reported at a number of championship shows, a certain cause of restricted movement. The judge at the Welsh Beagle Club’s November 2009 show wrote ‘I am saddened by the state of the breed at present particularly in males…I found many exhibits with large splayed feet and, accompanied by a weakness in pastern…’ This is not good news for any hound breed.

Long Distance Runner

In his informative book Beagling, Faber and Faber, 1960, Lovell Hewitt, makes some instructive points on the construction of the little hound. He considered that Beagles were all too often judged on their fronts and criticized the desire for absolutely straight front legs. He pointed out that Squire Osbaldeston’s rightly famous stallion hound Furrier 1820 was only drafted to the Belvoir because he was not quite straight in front. He stressed that the Beagle was a long-distance runner not a sprinter, emphasizing the importance of strong well-muscled loins and quarters. He wrote that Beagles tend to become weedy with successive generations and a narrow chest was a warning of this. He liked the fuller waist and disliked dippy backs. He found that a hound with a short head also lacked persistence. He was strongly against the exaggerated cat’s foot, once the preference in the hunting kennels.

In Sweden, Norway and Finland, the Beagle is a popular dog for hunting; the Swedish Beagle Club being founded in 1953. In these Nordic countries the Beagle is hunted singly not in a pack and not just on hare; in addition to hare, in Finland on fox, in Sweden on fox and roe deer and in Norway on fox, roe deer and deer. Each year around 300 entries at field trials are made in both Sweden and Finland. In Sweden a Beagle cannot become a show champion unless it first gains the field trial champion award. In Britain, Beagles from the show world can gain a working certificate; for the packs there used to be beagle trials like the West Country Beagle trials in March each year. Perhaps it’s time for another Charlie Morton! He hunted a small pack of Beagles solely for rabbiting with the gun, from about 1877 to 1919; his pack consisting of three couples of sixteen inch hounds and often producing returns of over seventy rabbits a shoot. He never carried a horn, just used his rich deep voice. He worked his hounds two or three days a week but insisted on a day’s break between shoots. He never used a van or a hound trailer, walking his hounds to each meet. Many of his hounds lived to well over ten and he hunted his pack for over forty years. Local farmers greatly valued his work on rabbit-control; rabbit damage in Britain nowadays costs our economy tens of millions of pounds. Bring back the Beagle-shoots!

“Since starting these annual shows at Peterborough and the formation of the stud-book, a marvellous change for the better has taken place in both the harrier and the beagle, but in the present instance, of course, my remarks must be confined to the latter. No beagle can now be entered in the stud-book with a direct harrier cross nearer than two generations back. Under the association, classes are arranged at the annual show for beagles not over sixteen inches which are entered in or are eligible for admission into the stud-book, and during the year 1893 there was a strong entry of these hounds. Leaving the association, I will endeavour to describe the best kind of beagle for hunting the hare, and I may remark that the little beagle of about twelve or thirteen inches, very pretty, and useful for rabbit hunting, is absolutely of no use whatsoever.”

From Hunting by the Duke of Beaufort (and seven other hound experts of that time), 1894.

“There are at the present moment, according to the Rural Almanack, 119 packs of harriers in England, 2 in Scotland, and 28 in Ireland, making a total of 149 for the United Kingdom; and there are 48 packs of beagles…Sir W Harcourt’s Act ‘For the better protection of occupiers of land against injury to their crops from ground game’, or ‘The Hares and Rabbits Bill’ was passed in 1880; and everybody knows the enormous destruction of hares which took place as soon as that Act came into operation; in many places, indeed, they became practically extinct…” (Going on the state the sportsman’s role subsequently in increasing hare numbers).

From The Encyclopaedia of Sport by The Earl of Suffolk, 1897.

“To sum up, therefore, which we should look for in our favourite hounds are perfect symmetry of build to insure strength and staying power, an intelligent and alert expression, a shapely neck, well-balanced shoulders, a compact sturdy body with good depth and width of chest, well-rounded and muscular loins and thighs and straight well-boned forelegs with perfect cat-feet. Of faults silently to shudder at, when seen in a neighbouring pack, and to turn a blind eye to, if seen in our own, are tendencies to straight shoulders, flat open splay feet, short throaty bull-necks, weak thighs, slack loins and flat sides, while knock knees with knees turned in and toes out or calf-knees with knees over-extended and actually bent slightly backwards, cannot fail to make us groan aloud in any circumstances in sympathy for the poor hound which possesses them.”

From Beagling for Beginners by Dr. D. Jobson-Scott OBE, MC, MD, Ch B, Hutchinson, 1933.