339 Losing Old Skills

LOSING OLD SKILLS

by David Hancock

.jpg)

Nostalgia, as Simone Signoret wrote in 1978, isn't what it used to be. And whilst the remembrance of the past as always being better than today does not withstand scrutiny, the loss of old skills merits mourning. My first contact with real dog-men came from living as a boy a few miles from a gypsy encampment, where they used lurchers and water-dogs in all sorts of skilful ways. It was a case of age-old skills being perpetuated by knowledgeable country people using clever dogs. I was privileged to have known them and learned so much from them, without their ever realising their teaching skills.

Nostalgia, as Simone Signoret wrote in 1978, isn't what it used to be. And whilst the remembrance of the past as always being better than today does not withstand scrutiny, the loss of old skills merits mourning. My first contact with real dog-men came from living as a boy a few miles from a gypsy encampment, where they used lurchers and water-dogs in all sorts of skilful ways. It was a case of age-old skills being perpetuated by knowledgeable country people using clever dogs. I was privileged to have known them and learned so much from them, without their ever realising their teaching skills.

Similarly, as a teenaged kennel-boy to my local vet, I learned by listening and watching. He was the Vet to the Bath Dog Show and when he toured the rings or examined exhibits, he explained the differences in construction between sighthounds and scenthounds, spaniels and Sealyhams. I now realise what a superb grounding this was. He knew what sporting and working dogs needed in order to carry out their function. Few vets seem to work dogs nowadays or understand the relationship between function and anatomy.

I was lucky enough to serve in a West Country regiment in the Malayan Emergency, where infantry patrolling was described by one wit as 'rough shooting supported by artillery.' The west country soldiers were mainly from a country background, with admirable attributes for the jungle like patience, knowledge of fieldcraft, being used to carrying a weapon and an ability to move silently. Even the reinforcing Geordies and Tykes came from pit-villages and a background of whippet-racing, poaching and terrier digs. We quickly realised that the issue American M1 point 300" carbine didn't penetrate dense undergrowth. I carried a Remington pump-gun; a colleague, a renowned shot, carried his private double-barrelled shotgun.

Nowadays such weapons would probably have to be conveyed in a sealed steel cabinet on your back! But country ways and country knowledge did contribute to military skill. I learned how to track from the Ibans, headhunters from Borneo, attached to each platoon. When you came across human tracks, the Iban tracker was asked two questions: Brapa orang (how many men) and Brapa hari (how many days)? These skilful men could tell you the size of the enemy party and how recently they had used this route. I learned too from an ex-deer stalker when training the battalion snipers on Dartmoor and from an elderly Forstmeisster when learning to operate in coniferous woods.

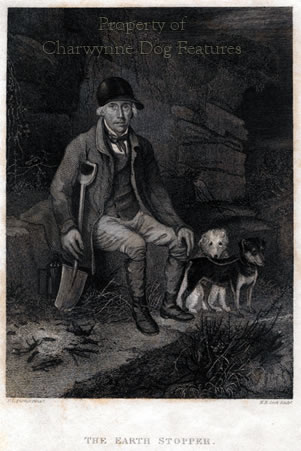

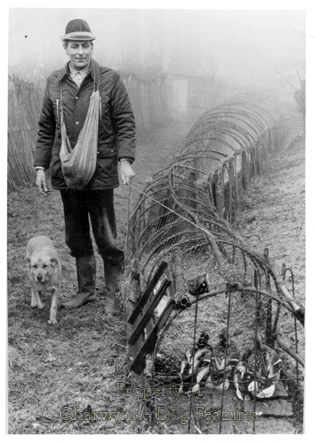

Old skills can of course be passed on or even relearned. But sometimes knowledgeable old countrymen can be hard to get on with. In the early days of game fairs I used to give a lift to them to a retired gamekeeper who lived nearby. He was quite the rudest man I have ever met -- but packed with knowledge. His pet hate appeared to be books on spaniel training; I had worries over whole stalls being demolished. "Nothing new said in 'undred years" he would bawl. He may well have a point. But he had a wonderful 'eye' for a dog, even puppies. He seemed to be able to spot a potential winner whilst the rest of us truly just guessed. .jpg)

I was privileged, in the 1980s, to make the acquaintance of a remarkable Dutch lady, Ploon de Raad, author of "Jachthonden", published in 1990. She had an understanding of gundogs which is rare. Not from her endless descriptions of gundog performance from long-forgotten field trials but insight into how such activity occurred. There are so many gundog writers with the ability to recall the past, flash their extensive experiences past you and offer opinions on every topic. Ploon de Raad was better than that; she knew why things happened. Perhaps having been a prisoner of the Japanese she knew better how to utilise experience. Knowledge without understanding is incomplete.

Twenty years ago, I used to have long conversations with that fascinating old terrierman Bert Gripton. Bert could give the word 'curmudgeonly' a bad name! He was once so outrageously rude to a fellow terrier fancier that those of us present just laughed out loud. But he was still worth listening to; he was rightly famous throughout the international terrier world. The son of a gamekeeper, he had been a groom at Badminton, a trumpeter in the Royal Horse Artillery, a pest controller for the Ministry of Agriculture and finally worked for a footwear firm, which allowed him to keep his big van on retirement for his terrier-transport. Bert said that his terrier knowledge came from an old gypsy, a Mr Baker, terrierman to the Albrighton.

Bert believed that no two terriers worked the same. He claimed that a real terrierman should be able to identify his underground quarry from the baying of his dogs, as it differs when faced with rabbit, fox or badger. He had a long connection with otter-hunting, beginning with the Hawkstone and then moving to the Border Counties. He once said that the irresponsible and boastful terrier owners do more harm than any opponent of field sports. I believe he was once a member of the Jack Russell Club early on in its life but gave up out of his dislike of its heavy commitment to showing. He spoke to me of producing a book one day. It would have been worth reading.

How I wish I had had the chance to meet other revered terriermen: Ralph Hodgson of Durham, Lewsyn Blucher of the Bwllfa pack, Arthur Heinemann of Devon and OT Price. Ralph Hodgson began to follow the Braes of Derwent at the age of ten in 1909, purchasing his first terrier, a Sealyham/Wire-haired Fox terrier cross in 1916. In time his unique skills at terrier rescue paved the way for some memorable terrier rescues in the Durham area. Lewsyn Blucher, as W Lewis Williams was better known, died in 1940, after a life spent hunting and fox catching by way of hound, terrier, trap, gun and snare. He was expert in the use of the 'Gist' trap. He favoured short-legged rough-coated terriers, presumably now lost to us.

Arthur Heinemann is better known to us. He has been described as the most important breeder of Jack Russell terriers after the parson's death. At a court case in 1923, Heinemann con vinced the judge that the Jack Russell was a bone fide breed of terrier, producing pedigrees dating back to 1890. He stated that: "We are very much opposed to the modern show terrier and his type. Once you begin to breed it for show type you lose the working qualities upon which you pride those terriers. I have been, I might say, the protagonist of the terrier bred for sport as against the terrier bred for show. I have no interest in cup hunting." Despite those remarks he became a Crufts judge but when he died in 1930 left behind a much-respected line of working terriers. Much of his knowledge died with him.

vinced the judge that the Jack Russell was a bone fide breed of terrier, producing pedigrees dating back to 1890. He stated that: "We are very much opposed to the modern show terrier and his type. Once you begin to breed it for show type you lose the working qualities upon which you pride those terriers. I have been, I might say, the protagonist of the terrier bred for sport as against the terrier bred for show. I have no interest in cup hunting." Despite those remarks he became a Crufts judge but when he died in 1930 left behind a much-respected line of working terriers. Much of his knowledge died with him.

We are lucky that Fred Goss, the renowned stag harbourer, gave us his "Memoirs of a Stag Harbourer", published by Witherby in 1931 and more recently by Halsgrove. His description of tracking deer reminds me so much of how Ibans interpreted human tracks in the jungle. Goss wrote: "The weight of a heavy stag coming on the ground also opens out the heel to an extent not seen in young stags. Thus the slot of a big heavy stag should be practically square. Each claw of a good warrantable stag should be at least an inch wide, but the measurement of the slot as a whole will, as previously indicated, depend to some extent on the soil in which it is planted."

Perhaps only when an asteroid hits the planet Earth and we are all forced to be hunters once more will the skill of men like these be valued. Valueless opinions can be obtained any day on the greatly over-rated internet, more a source of gossip than genuine corroborated factual knowledge. Any fool it seems can post what he considers 'information' on this source, unencumbered by research, editors or informants. Just like evaluating intelligence in battle, the grading of it is as important as the source. So many of the old-time experts knew how to sort 'the wheat from the chaff', but now I can be accused of saying that progress, just as Simone Signoret did of nostalgia, isn't what it used to be!