444 Before Breeds

BEFORE THERE WERE BREEDS

by David Hancock

When did breeds start? Hasn't every breed, including those claimed to be centuries-old, truly only been a breed since closed gene pools and registration were introduced? Breed historians so often claim ancient origins for their chosen breed, sometimes seeing an early depiction as proof of a breed's existence and electing to see mention of a canine function as proof of a breed's presence. The use of the word 'bulldogge', for example, to describe a function is so often confused with the word 'Bulldog', a breed title. The word 'borzoi' was once used to denote a fast-running dog, not a breed. The word 'mastiff' was once used to describe any large strapping dog. The terms staghound and minkhound denote functions not breeds. It is not wise to seek breed-origins in functional descriptions, although breed-type originated in function.

When did breeds start? Hasn't every breed, including those claimed to be centuries-old, truly only been a breed since closed gene pools and registration were introduced? Breed historians so often claim ancient origins for their chosen breed, sometimes seeing an early depiction as proof of a breed's existence and electing to see mention of a canine function as proof of a breed's presence. The use of the word 'bulldogge', for example, to describe a function is so often confused with the word 'Bulldog', a breed title. The word 'borzoi' was once used to denote a fast-running dog, not a breed. The word 'mastiff' was once used to describe any large strapping dog. The terms staghound and minkhound denote functions not breeds. It is not wise to seek breed-origins in functional descriptions, although breed-type originated in function.

In 1576, Abraham Fleming, 'newly drew into English' as he put it, Dr Caius's now-famous treatise, written in Latin, entitled 'Of English Dogs'. Dr Caius was no expert on dogs and undoubtedly had his leg pulled by the sportsmen of his day. Fleming too had no personal knowledge of dogs and interpreted Caius's words to suit himself. He certainly didn't help any researcher by using words like 'prosopopoical'! Fleming named the Harrier but described it as loose-lipped and long-eared and used to hunt eleven species, from polecats to lobsters! He named the Bloodhound but stated it was used to hunt cattle and follow the otter, perhaps meaning an all-purpose tracking hound excelling on blood trails. He named the gazehound, not as a sighthound but as a par force hound, used in packs by horsemen, not in a brace by a dismounted hunter.

Is it sound research therefore to regard the references in this treatise to be referring to the contemporary distinct breeds of Harrier and Bloodhound or to be considering the word gazehound to be synonymous with sighthound? The treatise also mentions the Mastiff or Bandog and separately the Molossus, clearly not considering the former to be the same as the latter. Yet since then, time and time again, the Mastiff is listed as a Molosser. Fleming does not describe such a dog as having a distinctive appearance but through its varied functions: to hunt the fox and the badger, to herd wild swine, to bait and take the bull by the ear and as a guardian of property. But nearly two centuries earlier, on mainland Europe, the mastiff was described as 'a manner of hound'; the word meant not a breed but a large dog of mixed breeding.

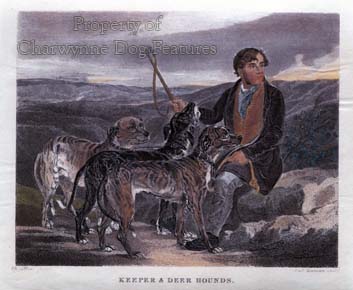

As Anne Rooney sets out in her 'Hunting in Middle English Literature' (Boydell, 1993), there are many references to deerhounds. But these are mentions of smooth-haired packhounds not rough-haired sighthounds from Scotland. The words describe the function not a breed. But I have seen them quoted by writers on Deerhounds as examples of an ancient employment for the modern breed. Our ancestors had no use for breeds but plenty of use for dogs in a specialised way. The pursuit of improved performance led Foxhounds to be crossed with Pointers and Bulldogs with Greyhounds. Excellence of function was all; purity of breeding was not worshipped. The latter half of the 19th century changed all that..jpg)

As Gilbert Leighton-Boyce writes in his masterly 'A Survey of Early Setters' of 1985: "The first properly organised dog show was held in 1859 and was limited to pointers and setters. The first field trial, which was confined to the same breeds, was held in 1865. Specialized animals began to be bred specifically and exclusively to win at these events, regardless of what it meant to other aspects of the animals' life and their relationship with their owners. At about the same period the pet-dog approach began to make itself felt as a different influence, which also could not be said to be entirely for the good. Be that as it may, a new era for setters had begun." This new era, not confined to setters of course, meant that dogs had to be registered in order to compete and so breeding was conducted to replicate breed distinctions rather than pure function. In field trials, function was the leading edge in breeding programmes but in the show world, beauty of form led the way. Breed distinctiveness became prized.

In The Kennel Club's Illustrated Breed Standards (Ebury Press, 2003) the Saluki is alleged to have been owned by sheikhs who have carefully kept records of his breeding and hunting abilities for hundreds of years. But if you read the authoritative 'Dogs in Antiquity' by Brewer, Clark and Phillips of 2001, you can see a rather different dimension. The Saluki was prized not because of its pedigree but its prowess. To improve its scenting ability the Saluki was crossed with the Kurdish sheepdog to produce a Khilasi, for example. In southern Arabia, the sheikhs produced a type more like a pariah dog to hunt ibex as a packhound, rather than course them with sighthounds. Such dogs have been written up as Salukis. One Arab scholar translated the writings of the ancient Greeks on dogs by substituting the word Saluki for Laconian Hound in his own work. When working in the Middle East I have not become aware of any ancient breeding records being maintained by sheikhs on their hunting dogs. They bred for field performance.

Field performance too led to the decoy dogs or tumblers being valued and the water-dogs being prized. Before the development of firearms, such dogs could mean the difference between eating and starving. Today these dogs are cherished because of their appearance not their cleverness, with separate breeds coming into being from Holland across to Russia and from Britain down to the Mediterranean. Handsome breeds like the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever and the Wetterhoun and Kooikerhondje from Holland grace our show rings; centuries before they were known as breeds, they were helping to feed hungry families. Water-dogs which could catch fish or retrieve bolts or arrows and decoy-dogs which could lure wildfowl into cages or nets had a very high value for the medieval hunter.

Has their being developed as breeds made them better dogs? In the past, good dog was bred to good dog because their usefulness was prized. Nowadays we breed winning dog to winning dog irrespective of their usefulness. We could be breeding in handsomeness at the expense of usefulness. Because a dog looks like a certain breed doesn't necessarily mean it can carry out the desired function of that breed. Is belonging to a breed solely a matter of appearance? Do breed instincts not matter too? When dog-walking I often meet owners of gundogs exercising their dogs. One has two Cocker Spaniels which really work the hedgerows, tails waving with enthusiasm, noses avidly seeking scent. Another has a Pointer which gets absolutely no thrill from scent at all; it shows nil interest in feathered game on the ground and remarkable disinterest in seeking air-scent. It only looks like a Pointer.

Does it benefit a breed when a gundog with upright shoulders, short upper arms, a distinct lack of lungroom and a long weak loin becomes a champion and then a much-used sire? I doubt if our ancestors, with their greater wisdom and better criteria, would have bred from such a dog. Without a functional test for a dog, we have come to rely solely on judges' decisions and individual breeders' preferred programmes for our future stock. But the show critiques indicate the folly of this in far too many breeds. Here are some judges' comments from Crufts 2004: Sussex Spaniels - How do some exhibits get past judges? American Cocker Spaniels - it seems to be when the dog moves the judge stops watching. Flat-coated Retrievers - I feel we are heading for a fast decline in our lovely breed. Irish Water Spaniels - Many may not be called on to do this work now, but that does not mean that the characteristic of the breed be overlooked in the show ring. Canaan Dog - I feel that it is essential that the breeders of such a new breed to the show ring should be the guardians of the breed characteristics developed over the centuries and not allow them to be watered down to provide them with a pretty show dog.

Before there were breeds, function played a far greater role in determining breeding stock. Perhaps it is time for the kennel clubs of the world to move on from being mere registries to act more as breed custodians. Gene pools have been established, that being the easy bit. Now is the time for organisations priding themselves on their self-proclaimed mandate of 'the improvement of dogs' to do just that. Breed clubs are at the mercy of individuals with questionable motives. Kennel clubs should be above character flaws in humans but forever eager to face up to a loss of breed characteristics in our precious breeds of dog. Any organisation which just goes on repeating the past and not adjusting to changing times is going to be overtaken by another.

As a nation in the process of destroying its world-renowned hunting dogs, we surely need to salvage something from such nihilism. Soon there may be no sporting breeds; the abolition of hunting dogs will progress, if that's the right word, to a campaign to ban shooting and more. Abolitionists get a taste for it. You can change your mind on the Poll Tax but you can't restore lost genes. The English philosopher John Locke wrote in 1690: "...the end of law is, not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom." Such words sadly do not feature in election manifestos but should feature in every law-maker's thought processes. But which presents the greater danger to sporting dogs, the abolition of hunting with dogs or the pursuit of closed gene pools in breeds of sporting dogs, which can seal in the faults? Our ancestors desired neither and handed down to us superlative canine athletes that are prized the world over.

It is significant that no MFH is content just to recycle the genes contained in his own pack. Each pack of Foxhounds is like a breed in itself. Centuries of selective breeding has taught Foxhound breeders that, in the perennial pursuit of excellence, it is important to renew, refresh, reinvigorate. The use of outside sires, the drafting in of hounds from other packs, even from America, and the introduction of new bitches, all contribute to the improvement, the enhanced performance of the pack. No pack of Foxhounds has a closed gene-pool. It would be a step forward if each pure breed of dog could be regarded as a pack of Foxhounds. In such a pack, breed-type is assured but both the phenotype and the genotype are considered worthy of improvement; better hounds are being sought each year not just the same old stock perpetuated more in hope than rationale.

As we choose as a nation to extinguish our hounds, acknowledged round the world as the best, we should at least attempt to extract some valuable lessons from this lengthy attainment of breeding success. The dogs bred by primitive hunters all over the world have been handed on to us, down the ages, for our care in our time. They bred good dog to good dog not just between two which looked the same and came from related parents. Breeds were created and then stabilized by superlative breeders, using time-honoured methods. Our methods, in modern times, are not time-honoured but have become accepted and approved by compliant brains, obedient minds, subservient souls. Closed gene pools may have been launched 150 years ago but that is but a tiny snatch of time in the long long history of man's striving to produce high-quality useful dogs.

In their quite excellent book 'Dogs' (Scribner, 2001), the Coppingers have written this plea: "Many breeds are living to pay a terrible price for the temporal increase in population or the luxury of expensive food and care. It is not simply that the dogs have access to the kind of medical care that is given to humans, but that they have been bred so they need such care to survive. Breeds like the bulldog are in a dead-end trap. There probably is not enough variation left to get them out of their genetic pickle. Unless the breed clubs open their stud books and allow outside breedings, bulldogs and other breeds caught in these eugenic breeding practices are headed for extinction." Raymond Coppinger is a professor of biology. Before there were breeds, dogs were bred to function.