527 THE EMERGENCE OF THE PASTORAL DOGS

THE EMERGENCE OF THE PASTORAL DOGS

by David Hancock

The Emergence of the Type by Function

The Emergence of the Type by Function

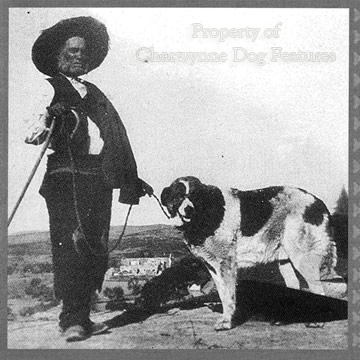

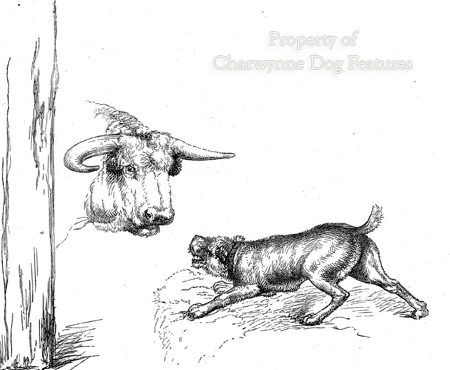

In his informative A History of Domesticated Animals (Hutchinson, 1963), the distinguished zoologist Frederick Zeuner wrote: “In the Bronze Age a moderately large dog is frequently found which, in many respects, is like some of the primitive breeds of sheepdog still to be found in parts of Europe. The modern collies, Alsatians and others with elongated skulls are products of very recent systematic breeding…In view of the palaeontological material now available, this means that the sheepdog group can be traced back to the Bronze Age…Its frequent occurrence in Bronze Age sites may be connected with the increasing importance of sheep-breeding in the economy of Bronze Age Europe. Thus the forerunners of the modern sheepdogs can so far be traced back to the Bronze Age only.” Evidence of far earlier use of pastoral dogs, not surprisingly, can be found in the artefacts of Ancient Egypt, as these two images demonstrate.

No Breed Identity

It is unwise for enthusiastic breed historians to link contemporary breeds with depictions of dogs on ancient artefacts. As Juliet Clutton-Brock wrote in her Domesticated Animals from early times, Heinemann (for The British Museum (Natural History), 1981: “The majority of the remains of the earliest domestic dogs have been retrieved from archaeological sites in western Asia, although small numbers have also been found in North and South America, north west Europe (England and Denmark), Russia and Japan. They are nowhere very common until the Neolithic period when livestock “The majority of the remains of the earliest domestic dogs have been retrieved from archaeological sites in western Asia, although small numbers have also been found in North and South America, north west Europe (England and Denmark), Russia and Japan. They are nowhere very common until the Neolithic period when livestock animals are of course also represented…The dogs of these early periods, before the invention or widespread use of agriculture, were already quite variable in size and they probably also varied in their pelage, length of ears and tail, and shape of facial region...it is not acceptable to divide these dog remains into separate categories or subspecies, let alone into breeds.” Function ensures physical resemblances but pure breeding for appearance is a modern phenomenon.

Usefulness to Man

If man is the most successful mammal on the planet, then, dog, man's closest animal companion, is arguably the second most successful and certainly man’s most valuable animal companion. Dogs have changed history, allowing for example early farmers to protect their livestock from predators, primitive hunters to obtain meat for the table and facilitate travel in Arctic conditions. In his Dogs: A Historical Journey (Howell Book House, 1996), Lloyd Wendt writes: 'The earliest evident pattern of human and dog migrations and partnership activity began in southeastern Africa, extending to Lakes Turkana and Omo in Ethiopia and the Nile tributaries, the Nile itself, and may have reached past the deserts of Sudan...' In his Dogs through History (Denlinger, 1987), Maxwell Riddle writes: 'Asia is a huge land mass, with high mountains separating fertile valleys. Such valleys were ideal for developing dog breeds. Their comparative isolation and highland stock grazing areas challenged the people within to produce dogs for specialized purposes.'

In her The Lost History of the Canine Race (Andrews and McMeel, 1996), Mary Thurston writes: 'At its height, Rome was a veritable melting pot of both domesticated animals and people...At the same time, "exotic" dogs continued to arrive from Northern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Out-crossed with one another as well as with the more primitive, Neolithic canines still residing in rural parts of Southern Europe, they gave rise to a plethora of new varieties...' These three quotes provide background to the timeless development of dogs with people, the movement of people with their dogs and the trading in dogs once their value was known.

The Farmers’ Needs

It was during the eighth and seventh millennia BC that man first began to domesticate sheep and goats within the region of Western Asia. Unlike nomadic animals such as gazelles, antelope and bison, humans, sheep, goats and dogs were all part of a social system based on a single dominant leader and tended to settle on what became known as a home range. They therefore became inter-dependent, with the herdsman as leader and the dog as his agent. Dogs also protected humans and their livestock against wild predators such as lynxes, lions, wolves, tigers, jackals, leopards, cheetahs, foxes, civets and, in some places, huge eagles. The protection of flock-guarding dogs was vital; such dogs had to be brave and determined, alert and resolute, vigilant and reactive – but above all, protective.

The Spread of Agriculture

In his Farmers in Prehistoric Britain of 2011, Francis Pryor gives the view that: “The spread of farming across Europe has been well documented by excavation and radiocarbon dating. At present it would appear that farming reached the north and west extremities of the continent by two distinct routes, or groups of routes: overland by way of the Danube and Rhine valleys to modern Germany, northern France and the Low Countries; or via the Mediterranean to the Alps, or up the Rhone into central and northern France or, finally, across south-western France via the Carcasonne-Narbonne ‘gap’.' Pryor estimates that there may well have been as many as 5,000 sheep in just one fen basin, Flag Fen basin, in the Bronze Age in Britain. If such sheep farming here involved sheepdogs and the routes above were followed by farmers with dogs, it is easy to see how their pastoral dogs ended up in the nations of today covered by these routes and perhaps why, in time, such dogs ended up resembling each other.

Roles for Pastoral Dogs

Not surprisingly, the dogs that protected flocks of sheep from wild predators, human rustlers or other dogs were large and fierce. Those that controlled the flock or herd were smaller, more biddable, and, although less fierce, were still very resolute, such as the German Shepherd Dog – used as a ‘living fence’. The driving dogs combined stamina and robustness with an instinctive desire to keep the flock or herd together as a group. The herding or penning dogs were required to be highly responsive to the human voice or whistle and yet still be very strong-willed. British breeds have long excelled in this role. The heeling dogs were used to turn or drive cattle and had to be small, quick and extremely agile, as the Corgi breeds demonstrate to this day. The pinning or gripping dogs, once hunting dogs and utilized extensively by butchers, were needed to seize and hold one individual animal, for example a powerful sow, to facilitate handling, loading on to transport or even slaughter. Broad-mouthed breeds like the old type of Bulldog, the Cane Corso of Italy and the Rottweiler of Germany were used for this type of work, valued for their fierce determination and widely traded.

Dog-traders have earned themselves a questionable reputation in modern times, but trading in dogs in past times allowed the widespread movement of dogs and a wider appreciation of their usefulness. Dogs accompanied wandering tribes, campaigning armies and migrating peoples, provided they had some use. The game-catchers like the sighthound breeds, the game-finders like the modern gundog breeds and the flock guarding breeds each had a distinct value to man. The need to control vermin led to the development of the terrier breeds. The need to control sheep gave us the herding breeds. Dogs that excelled in their specialist function have long been extensively traded. In due course, dogs that worked with livestock went with that livestock, even across national boundaries and on ships sailing to the colonies. That is how many pastoral breeds developed eventually as separate distinct breeds once modified by local conditions overseas. But wherever they went they had to function.

Needs of the Role

Whatever their role, their work, the climate and the terrain demanded excellent feet, tough frames, weatherproof coats, enormous stamina, really good eyesight and hearing and quite remarkable robustness. These dogs operated in harsh conditions, ranging from the hottest to the coldest, the stoniest, thorniest, windiest, most mountainous and most arid areas of Europe and Western Asia. Farmers and shepherds had to have entirely functional dogs; physical exaggeration does not occur in any of the flock-guarding breeds, unlike the ornamental ones. Hunting ability was not desired although the physical power and bravery of such dogs did lead to their use in bear hunts in Russia and boar hunts in Central Europe, where they were used at the kill, not in the hunt itself. The demands of climate have led to both the flock guardians and the shepherd dogs featuring appropriate coats for their region. The Hungarian Komondor and the Italian Bergamasco display the thick corded or felted coats required to survive in their working environment. The Swiss Entlebucher and Appenzeller and the New Zealand Huntaway exhibit the smooth sleek coats best suited to their working conditions.

If we then look at the shorter legs of the heeling breeds, like the Corgis, and the longer legs of the herding dogs, like the Belgian, Dutch and German Shepherd Dogs, we can see how not only climate but also terrain and function determined type. In some areas the harsh-haired or goat-haired breeds, like the Bearded Collie and the Schapendoes of Holland, were favoured, because of the local conditions and their instinctive skills. The breeds were shaped by the farmers’ needs. Wherever they worked or farmed, farmers needed dogs with the innate characteristics, the appropriate physique and the suitable length and texture of coat to protect, drive or herd their stock, hunt down vermin and guard their farmsteads and pastures. Their demanding requirements have left us with some of the most popular breeds of companion dog today, although, sadly, these are so often bred more with cosmetic than functional considerations in today’s society. In order to appreciate the extraordinary value of the pastoral dogs of the recent past, it is worth a study of the drovers and their dogs – transhumance in Britain.

The Drovers and Their Dogs

“…for centuries, at least from the time of the Norman conquest to the establishment of the railways, the most important long-distance travellers were the drovers…they formed great cavalcades that blocked the way for other travellers for hours at a time…if farmers did not want their cattle to join the drove they had to make sure they were safely enclosed…Some parts of the drove-ways were also used to transport pigs, sheep, geese and turkeys, and these animals also had to travel great distances.” Those words from Shirley Toulson’s The Drovers (Shire Publications, 1980) provide an immediate concept of the significance of historic markets and the total reliance on dogs to get the livestock to market. It’s difficult to visualize nowadays six thousand sheep being moved on foot in more or less one huge flock from east of the Pennines to the markets of Norfolk and Smithfield. It’s not easy to think of thousands of cattle, sheep and even geese being shepherded by a small number of dogs from remote rural pastures along established drove-roads to city markets – and the dogs either accompanying the mounted drover homewards or then being left to find their own way home. These were very remarkable dogs.

In his Cynographia Britannica of 1800, Sydenham Edwards writes, of the drover’s dog: “…he appears peculiar to England, being rarely found even in Scotland. He is useful to the farmer or grazier, for watching or driving their cattle, and to the drover and butcher for driving cattle and sheep to slaughter; he is sagacious, fond of employment, and active; if a drove is huddled together so as to retard their progress, he dashes amongst and separates them till they form a line and travel more commodiously; if a sheep is refractory and runs wild, he soon overtakes and seizes him by the foreleg or ear, pulls him to the ground. The bull or ox he forces into obedience by keen bites on the heels or tail, and most dexterously avoids their kicks. He knows his master’s grounds, and is a rigid centinel on duty, never suffering them to break their bounds, or strangers to enter. He shakes the intruding hog by the ear, and obliges him to quit the territories. He bears blows and kicks with much philosophy…” Those picturesque words are a concise summary of the dogs’ purpose, as well as showing their prowess as heelers too.

In his The Dog of 1854, Youatt wrote, on the drover’s dog: “He bears considerable resemblance to the Sheepdog, and has usually the same prevailing black or brown colour. He possesses all the docility of the Sheepdog, with more courage, and sometimes ferocity.” The drover’s dog would have needed ferocity to keep an endless stream of village curs from attacking the flock, great courage in facing every kind of obstacle and threat en route to the ‘fattening fields’ and the docility to obey every command from the accompanying drover whilst ignoring rustlers, thieves or the wrath of inconvenienced citizens finding their path blocked. Such dogs had to think for themselves, in the modern idiom, ‘think on their feet’. From that background come the gifted sheepdogs of today.

In his British Dogs of1888, Hugh Dalziel wrote: “In all parts of England and Scotland I have seen drovers, and narrowly scanned their dogs, and I have come to the conclusion that no distinct breed can be justly described as the Drover’s Dog, but that the latter, like the poacher’s dog, the Lurcher, may be compounded of many varieties, the drover utilising for his purpose the kind of dog that comes most readily to hand.” These few words on such important dogs indicate the wide gulf between the educated classes and the peasant-shepherd over dogs; the better-off, especially the landed gentry sought style and followed fashion in their gundogs and hounds. The peasant-shepherds needed performance and were content with utility in their dogs. In books on dogs in the 19th century the pastoral dogs were rarely covered in any detail or indeed accuracy.

In his three volume work, Dalziel also wrote: “The English Sheepdog, as I recognize him, and as he is seen with the shepherd on the South Downs, on the Salisbury Plains, and on the Welsh, Cumbrian, and Scotch hills and dales, is usually, but not invariably, bob-tailed – either born so, or made so by docking. I have in vain consulted past writers on dogs for any minute description of this animal’s size, build, general appearance, and, in show language, his ‘points’.” From this background, with its lack of familiarity with its subject, it is never easy to research the pastoral breeds, either here or abroad.

Changed World

The advent of the pedigree dog show in the middle of the 19th century changed the world of the domestic dog forever. For the very first time, the working, pastoral and sporting breeds were to be judged on what they looked like rather than what they could do. A handsome but brainless, motiveless dog could be rated as more valuable than a skilful hard-working sheepdog serving its master in all winds and weather in harsh unforgiving terrain. A determination to ‘stamp out the drover’s dog’, as Weager (below) put it, eventually came into every pastoral breed:

“OLD ENGLISH SHEEPDOGS

The increased interest now taken in this, one of the most useful and picturesque of English dogs, was apparent at the Kennel Club show, where more purchases were effected and higher prices realized than in any other class. Farmers and others will do well to look about them and send dogs to shows, where they will find a ready market for good specimens. The quality of the dogs shown on this occasion has greatly improved on the corresponding exhibition of last year. The club’s determination to stamp out the drover’s dog has been most effectual, and here on this event was only one wrong specimen shown.”

William G Weager, The Kennel Gazette, February, 1889.

The ‘wrong specimen’, as Weager termed it, might well have been highly effective herding or driving dogs but were not as handsome as the ringside viewing expected. Judging dogs entirely on their appearance is not exactly a rational act but sadly so often a wallet-led human choice. The exhibiting of dogs too has led to some pastoral breeds being seen much more often in towns than was once the case. It is noteworthy that the pastoral breeds of Britain were very much the dogs of working people. Early photographs of rural communities illustrate this fact. If you read Victorian dog books, packed with chapters on hounds and gundogs, you quickly detect a lack of real knowledge from the monied, educated classes of these humbler but certainly more valuable canine workers.

A number of pastoral breed-types never reached the show ring, perhaps lacking the glamour that the public seek in their canine pets. Most of the old Welsh breeds were lost to us, and the Smithfield Sheepdog is only kept going by the lurcher fraternity – and in Tasmania! The small heeler types of England vanished too, although eventually the Ormskirk Heeler was reclaimed for us and named the Lancashire Heeler. Undoubtedly, the show ring saved some pastoral breeds, even if many were changed morphologically and not to their benefit. Depictions of the pastoral breeds of a century ago show very different creatures from their counterparts today. The pastoral dogs that emerged across the globe were shaped by function, climate and terrain; this gave us the precious and valuable pastoral breeds we treasure today. We must honour their origins and breed them to reflect that.