678 OVERLOOKED SPANIELS

OVERLOOKED SPANIELS

by David Hancock

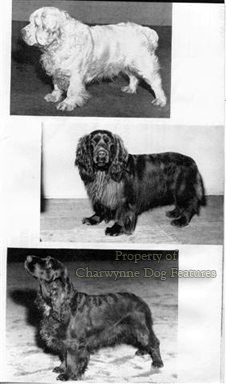

If you glanced at the annual registrations of spaniels with the Kennel Club you would be impressed by the sheer number being bred each year: some 38,000. But if you then take away the totals for two particular breeds, the English Springer and the Cocker, you would be left with less than a thousand registrations from all the other sporting spaniel breeds. Of four of the land spaniel breeds, the Welsh Springer can reach around 500 each year, but the remaining three give cause for serious concern. For the Clumber, with only around 200 registrations a year, the outlook is worrying. For the Sussex, with just over 50, and the Field, with around 75, the outlook is dire. These two old British gundog breeds deserve our support. In 1908 over 280 Field Spaniels were registered with the KC, against less than 50 English Springers; the Sussex Spaniel was a dying breed even then. In the shooting field the English Springers and the Cockers now rule the roost. But I see so much to admire in the handsome springer from Wales, the distinctive spaniel from Sussex and the fussless Fields.

If you glanced at the annual registrations of spaniels with the Kennel Club you would be impressed by the sheer number being bred each year: some 38,000. But if you then take away the totals for two particular breeds, the English Springer and the Cocker, you would be left with less than a thousand registrations from all the other sporting spaniel breeds. Of four of the land spaniel breeds, the Welsh Springer can reach around 500 each year, but the remaining three give cause for serious concern. For the Clumber, with only around 200 registrations a year, the outlook is worrying. For the Sussex, with just over 50, and the Field, with around 75, the outlook is dire. These two old British gundog breeds deserve our support. In 1908 over 280 Field Spaniels were registered with the KC, against less than 50 English Springers; the Sussex Spaniel was a dying breed even then. In the shooting field the English Springers and the Cockers now rule the roost. But I see so much to admire in the handsome springer from Wales, the distinctive spaniel from Sussex and the fussless Fields.

It is not always easy to recommend a breed of gundog to an individual, what with differences of terrain, temperament, quarry and handler-capability. But when the country being shot over calls for the resolute flushing of game, then give me one of the old-fashioned spaniel breeds, ideally a Field Spaniel of say Rhiwlas breeding. A combination of low-growing bramble and bracken or thick gorse is more than a match for a fast whippety field-trials’ dog, whose instinct may be to try to go over dense prickly undergrowth rather than get his head right down and bore his own trail. A sturdy Field Spaniel with a powerful low drive is the breed for such a task.

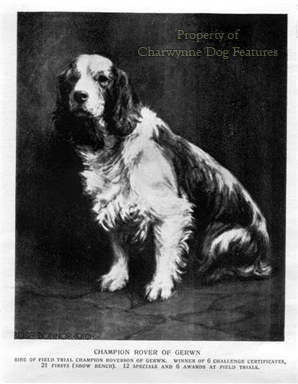

In making a plea to the shooting fraternity to utilise this admirable breed more, my mind goes back to a story told by that great spaniel fancier CA Phillips. He was recalling an occasion in Ireland in the 1920s when the Kildare hounds were drawing the new gorse at Castletown and finding it most difficult to work, with no foxes prepared to bolt for them. Colonel Claude Cane, from his adjoining property, teased the Master and said his spaniels would shift them. Invited by the Master to attend next time, Colonel Cane did so with six spaniels, four of them being black Fields, all well-known show winners, one of them Champion Celbridge Chloe. With hounds and field gathered together some distance away, the spaniels were sent in. A good deal of ribald comment came from the hunting people, but, in only a few minutes, out came not just pheasants, rabbits and the odd hare, but no less than six foxes and a grateful hunting field set off in pursuit.

The Field Spaniel may well be the truest model for all our modern English breeds of land spaniels. This breed is the sturdy active contemporary version of the old sporting spaniel. To avoid confusion between Field (the name of the breed) and field spaniels (spaniels used in the field) it might have been preferable to have named this breed ‘The English Land Spaniel’. The present title is rather a nondescript name for a breed that is anything but nondescript. Today’s lively, well-proportioned, fine looking breed certainly merits a suitably distinctive name. Field Spaniels have made enormous strides in physical conformation since the antics of their fanciers of the 1890-1900 period, the peak of the ‘bassetized era’, in which a needlessly low stature was favoured. Then, exhibitors could be seen at shows actually aiming to impress the breed judge with the sheer length of their entry, to claim on one occasion, that Rother Queen was half an inch longer in the back than Undeniable, as a point of merit in a working gundog! Sometimes the greatest threat to a breed’s well-being comes from its own fanciers.

The Field Spaniel comes in a variety of colours: black, liver or roan, with the liver and whites revealing the approved outcross to the English Springer. Two inches lower at the withers, in a richer golden liver only, comes the Sussex Spaniel. If the Field is a little tank in heavy cover, the Sussex is a little bulldozer. The latter is employed to find and flush game, can give tongue when hunting and can be slow-maturing and strong-willed, not the gundog for the impatient or short-tempered. For me, this breed can be handicapped by its ownbreed standard; who seeks a rolling gait in their sporting dog? Who wants a frowning dog? Who, in these days of obese dogs desires a gundog without a waistline? I am pleased that the Kennel Club has recently removed the word ‘massive’ from the general appearance section and the word ‘much’ from the phrase ‘not showing much haw’. A rolling gait can put extra stress on the hindquarters; a frown can soon become an overlapping fold which hampers vision. Does the presence of a waistline indicate a shelly, lightweight spaniel incapable of smashing through heavy cover? A balanced symmetrical build is sought in most sporting spaniels; why not in this one? Balance should be a top goal in breeding Sussex Spaniels.

The history of the breed standard of the Sussex Spaniel tells you a great deal about show gundog fanciers. The standard in use in 1879 didn’t include words like massive, brows and haw or mention a rolling gait. In 1890, in came ‘fairly heavy brows’, a ‘rather massive’ appearance and ‘not showing the haw overmuch’. In the 1920s, in came ‘brows frowning’, a ‘massive’ appearance and ‘no sign of waistiness’ in the body. These words were approved by the KC, the ratifiers of all breed standards. In 1890 the breed’s neck had to be ‘rather short’; from the 1920s it had to have a long neck – in the same breed! The need for this breed to walk with a rolling gait is, relative to the long history of this admirable little gundog breed, relatively recent. Here is a breed of sporting spaniel, developed by real gundog men,subsequently, with the connivance of the KC, altered to suit show dog people, most of whom never work their dogs. It is a sorry tale, with echoes in other breeds.

The so-called ‘Chocolate Drop’ spaniels of Richard Mace have their admirers in the field. Originating in a cross between a working Cocker and a Sussex Spaniel, they are seriously effective working spaniels, strong, biddable and determined. In the last ten years, pedigree Sussex Spaniels have only been registered in these numbers: 89, 98, 70, 82, 68, 79, 77, 74, 61 and most recently 56. What would you want? A dying breed prized for its unique rolling gait, characteristic frown and waistline-free torso? Or a proven worker benefiting from a blend of blood? Gundog breeds which lose their working role soon lose their working ability and then the patronage of the shooting fraternity. I see much to admire in the Sussex Spaniel and long for a wider emplyment for them in the field.

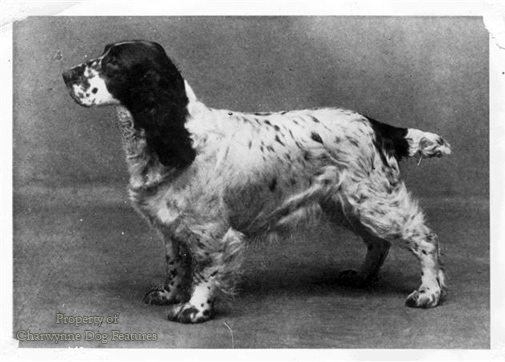

The sporting spaniel of Wales, their springer, gladdens my heart whenever I see them. They are so handsome with their rich red jackets, alert looking-for-work expression and their wholly unexaggerated anatomies. There is nothing overdone in this breed; symmetrically built, not over-coated, neither aggressive nor nervous and lacking any faddy undesirable breed features, they deserve wider use in the field and a stronger breeding base. This is not a spaniel breed under threat but still one deserving greater recognition by sportsmen. Linked by some with the Irish Red and White Setter and the Brittany, the Welsh Springer’s head is a main distinguishing feature. One eminent breeder from the past, Mr HC Payne of Monmouthshire, used to argue: “Cut off a Welshie’s head and all you’ve got left is just another spaniel.” Unless this splendid ancient breed is supported Wales could lose a distinctive worthy breed. Unless, in England, we value our Fields, Clumbers and Sussex Spaniels, they go too.