1062 FLOCK GUARDIANS IN IBERIA

FLOCK GUARDIANS IN IBERIA

by David Hancock

From Portugal in the west, right across to the Lebanon and then on to the Caucasus mountains in the east, from southern Greece, north through Hungary to most parts of Russia there are powerful pastoral dogs to be found, developed over thousands of years to protect man's domesticated animals from the attacks of wild animals. Some are called shepherd dogs, others mountain dogs and a few dubbed 'mastiffs', despite the conformation of their skulls. Their coat colours vary from pure white to wolf-grey and from a rich red to black and tan. Some are no longer used as herd-protectors and their numbers in north-west Europe dramatically decreased when the use of draught dogs lapsed. A number of common characteristics link these widely-separated breeds: a thick weatherproof coat, a powerful build, an independence of mind, a certain majesty and a strong instinct to protect. As a group, they would be most accurately described as the flock guardians. In North America they are usually referred to as Livestock Protection Dogs and sometimes elsewhere as shepherds' mastiffs. In many European countries, Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal, for example, such dogs were fitted with spiked collars to protect them in encounters with wolves or bears.

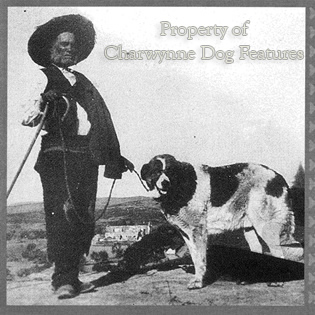

In south-west Europe these dogs became known in time as breeds such as the Estrela Mountain Dog, the Cao de Castro Laboreiro and the Rafeiro do Alentejo of Portugal and the Spanish or Extremadura 'Mastiff'. To the north-east of the Iberian peninsula, such dogs became known as the Pyrenean Mountain Dog or Patou, on the French side, and, separately, on the Spanish side, as the Pyrenean 'Mastiff'. In the Swiss Alps they divided, as different regions favoured different coat colours and textures into the 'sennenhund' or mountain pasture breeds we know today as the Bernese, Appenzell, Entlebuch and Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs and the Alpine Mastiff, which is behind the St Bernard, a breed once much more like the flock-guardian phenotype. In Italy, local shepherds favoured the pale colours now found in the Maremma Sheepdog and the very heavy coat of the Bergamasco. In the north-west of Italy, the Patua or Cane Garouf, the Italian Alpine Mastiff may soon be lost to us. In Corsica, their flock protector, the Cursinu, is also under threat as numbers fall. In the Balkans, similarly differing preferences led to the emergence of the all-white Greek sheepdog and the wolf-grey flock guardians of the former Yugoslavia, the Karst of Slovenia, the Tornjak or Croatian Guard Dog and the Sar Planninac of Macedonia.

Extensive trade was conducted between western Anatolia and the Mediterranean littoral, from southern Portugal and Spain to southern Italy and Greece. Valuable hunting and flock-guarding dogs would have been coveted and then traded. Agricultural and social change both affected the way the flock-guarding dogs developed and so too have climate and terrain. In Poland for example the Tatra Mountain Dog is a large thick-coated breed whereas the Portuguese breed of Rafeiro do Alentejo is lighter-coated but still sizeable. Man's dependence on huge dogs to guard his livestock is not however as dramatic as war and hunting and because shepherds were not usually literate, it rarely features in art or literature. Yet sheep migration alone has historic significance, both over the movement of people and their culture. The Foundation for Transhumance and Nature in Switzerland has estimated that there are 77,000 miles of sheep trails in the world, with each migration averaging from 370 to 620 miles. International boundaries had no importance.

It is forgiveable to believe that such breeds are sizeable because they need to be able to see off wild animals that prey on sheep. But much more important are the bigger stride afforded by size, the ability to carry more fat reserves and store more heat than a small dog and to survive disease, severe weather and the odd accident - big bones break less easily than tiny ones. This is why such breeds possess a similar phenotype; the Estrela Mountain Dog is easily confused with a Slovenian Karst, or the Spanish Mastiff with the Caucasian Owtcharka and, incidentally, with the created 'mountain dog breed' of Leonberger, or a Maremma with a Tatra Mountain Dog. The Caucasian Owtcharka can resemble the early St Bernards, the Alpine flock guardian, too. The shepherds, drovers, stockmen and traders in such dogs knew what made a dog effective and therefore more valuable. It is wrong however to breed for great size alone in such breeds, dogs on long migrations were 60lbs weight not the '100lbs plus' often desired in breeds like the St Bernard and the Newfoundland, that suffer badly in extreme heat. The warmer the migration route the lighter the dogs had to be to cope with the temperature. The more substantial dogs – with heftier frames, able to conserve heat – featured further north or purely in mountainous regions.

I have been impressed by the Portuguese livestock protection breeds and seen some of them at work. I was surprised to learn of a Portuguese judge, when judging his Estrela Mountain Dog entry at Bath Dog Show in 1978, refusing to judge a short-haired exhibit in the same class as the long-haired variety. Shortly after this incident, I was in Lisbon and called on the Clube Portugues de Canicultura, based there, for clarification. I was briefed that both the long and short-haired varieties are within their breed standard, but not interbred. This is to me a needless lessening of the gene pool and can only be yet another manifestation of the dreaded ‘pure-breeding’ mantra. The shepherds I talked to about this matter, just shrugged dismissively and expressed scorn at such a foolish distinction, never respected by them. Their dogs were smaller than the show entry here and those paraded at the World Dog Show held in Oporto and Lisbon in 2001. I asked the shepherds about the other Portuguese breed of this type, the Rafeiro do Alentejo; they pointed to a tawny-yellow solid-coloured dog lying nearby, saying that it was one and their favoured sire! (The others I saw elsewhere of this breed were bi-coloured, several were dappled.) They mentioned, with admiration a breed further north, the Cao de Gado Transmontana, often 30inches at the shoulder and used to get the cattle between summer and winter pastures. The Portuguese shepherds, like all shepherds before them, bred good dog to good dog; breed identity didn’t matter for them.

The ease of modern living has led to our devaluing the contribution made throughout human history by the flock protectors, but our ancestors prized them and developed them as highly impressive, extraordinarily robust, canine specimens. We must be careful with the surviving breeds not to substitute show-ring criteria for functional need. The Spanish Mastiffs I have viewed at World Dog Shows have mainly been seriously over-boned. Huge cow-hocked, straight-stifled, over-coated, under-muscled shepherd's mastiffs would not have lasted long in the demanding pastures of past centuries. Our respect both for our rural heritage and those breeds surviving man's changing requirements needs to be demonstrated by a seeking of soundness before ‘stance’ and fitness ahead of flashiness. These quite remarkable faithful, selfless, admirable dogs, often killed by marauding packs of predatory wolves, deserve no less. With around 330 sheep currently being killed annually by bears, reintroduced from the Czech Republic into the Pyrenees, perhaps the reintroduction too of the shepherd’s mastiff, more determined than the mountain dogs, would be timely.