807 RECASTING OUR BULLDOG

RECASTING OUR BULLDOG

by David Hancock

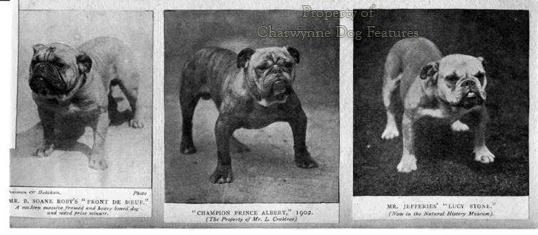

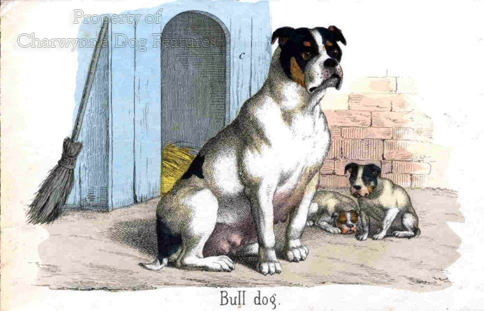

"Anyhow, the Bulldog of today is an entirely different animal, both physically and mentally, from the Bulldog of fifty years ago. Then he was a leggy, terrier-like, active brute...As to whether the fancier has improved the breed constitutionally is a moot point. Type has certainly been made more uniform; but this in many cases has been at the expense of other qualities."

'British Dogs' by WD Drury, 1903.

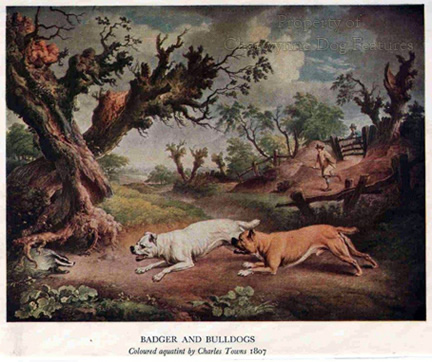

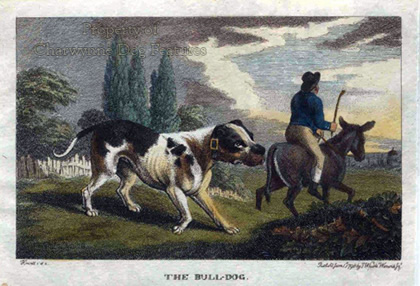

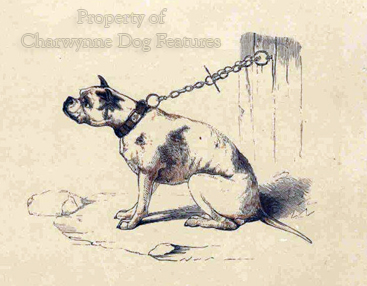

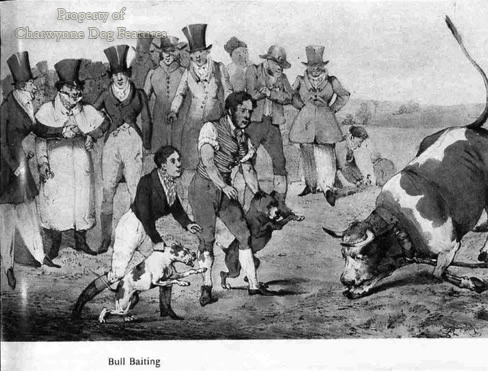

The Demands of Baiting

The barbaric sport of bull-baiting demanded the production of savage, ferocious, fearsomely aggressive dogs. Any thirty pound dog prepared to attack an enraged one ton bull has to be both extraordinarily brave and almost irrationally determined, valuable characteristics but not ones without dangers. A savage, aggressive, recklessly-brave dog, however much admired in its time, has a more limited future once an unpleasant recreation like bull-baiting is discontinued. Writing in his "The Bulldog - a Monograph" of 1899, Edgar Farman observed that: "From that time forward the breed began to deteriorate, and, with the era of modern dog shows, the appearance of an up-to-date specimen became a caricature of the active and plucky animal that baited the bull". This 'caricature' has sadly become the model for this admirable breed and harmed the breed for over a century.

Promoting Incapability

In his 'The British Dog' of 1888, Hugh Dalziel quotes the Bulldog and Mastiff fancier Adcock as stating: "In such a combat (i.e. bull-baiting) as this, it is needless to point out that the toy dog at present cherished by a few as the English Bulldog is - notwithstanding he is frequently possessed of unflinching courage - quite incapable of the part assigned him by Claudian and the subsequent writers; indeed, the dwarfed body and limbs would not only prevent his ever being able to catch an active and unfettered bull, but would also deprive him of the ability to make good his escape should he feel so disposed, whilst the absurd, excessive, and unnatural shortness of face would render a firm and lasting hold almost an impossibility." It is difficult to disagree with that last sentence. The baiting dogs were bred for performance, however regrettable, the show dogs were bred to suit human whim, not their physical comfort.

"...the bulldog was too slow for fighting...he could not get a mouth on quickly. Again, you must not confuse him with the modern creation, for man has so improved the short nose that these poor brutes can now hardly pick up their own food."

from 'Fighting Sports' by Captain L Fitz-Barnard (Reprint 1971)

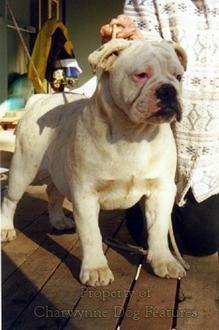

Crippled Abnormal Dogs

The last quarter of the nineteenth century sounded the death knell for the old bull-baiting type of Bulldog. In his "Dogs: their History and Development" of 1927, Edward Ash wrote: "When bull-baiting...ended, the dog was bred for 'fancy', and characteristics desired at earlier times for fighting and baiting purposes were exaggerated, so that the unfortunate dog became unhappily abnormal. In this translation stage huge, broad, ungainly heads were obtained, legs widely bowed were developed, and frequently the dog was a cripple." In the pursuit of a smaller, less aggressive animal, breeders resorted to the blood of the Pug, an equable companionable breed of great charm. No depiction of baiting dogs shows them featuring the short face. It's an inaccurate infliction.

The Introduction of Pug Blood

I know of only one book on the pure-bred Bulldog that acknowledges this cross and describes its undesirable consequences. This is the first book devoted to the breed, Robert Fulton's 'The Bulldog' of 1889, in which he states: "...I firmly believe the pug was in a measure used, judging from the structural formation of many specimens." It is flatly denied by Bulldog breeders today but all the authoritative writers on dogs at the end of the last century and at the start of this: Vero Shaw, Rawdon Lee, Sydenham Edwards, Robert Leighton and the celebrated 'Stonehenge', state that it did. How can any breed prosper in an atmosphere of deceit and harmful concealment? Outside blood can have value but only when it is planned for improvement rather than from some influential clique's whim. Bulldogs had to be swift, agile and athletic just to survive in the appalling world of baiting animals. The disgraceful treatment meted out to the baited animals gives you some idea of the so-called human beings involved in such barbarity. There are records of bears having their claws and teeth ripped out, bulls having hot oil poured in their ears, black pepper being thrust up their nostrils, having not just their tongues and noses cut out but their forelegs cut off to lower their height. Most of the baiting dogs suffered too.

Discomfort and Disadvantage

Some commentators, especially around Crufts time, suggest that the design of the Bulldog of today inflicts discomfort and disadvantage on the breed amounting to cruelty. Simon Wolfensohn, a practising vet, writing in the New Scientist nineteen years ago, listed, in the breed of Bulldog: respiratory problems due to the short nose, dental problems due to the short jaw, protusion of the upper or lower jaw, skin infections due to bacteria becoming trapped in the folds of the skin and problems giving birth. The authoritative "Medical and Genetic Aspects of Purebred Dogs" edited by Clark and Stainer, published by Forum Publications USA in 1994, states that only 6% of bitches whelp naturally, that of 707 pups delivered in 150 caesarean sections 37 had cleft palates and 58 of them died of walrus syndrome (three times normal birth weight). The book describes as "one of the most devastating conditions found in the Bulldog" foreleg lameness caused by loose shoulder joints and leading to severe chronic strain on the shoulder and elbow joints, resulting in debilitating foreleg arthritis. Since the breed standard requires the Bulldog to have forelegs set wide apart and elbows which stand well away from the ribs, such a problem is scarcely surprising. As this breed standard demands a dog with a massive head and hindquarters lighter in comparison with heavy foreparts, natural whelping is hardly assisted.

Impeded Powers of Locomotion

In his The Bulldog – A Monograph of 1899, Edgar Farman wrote: "The early show Bulldogs were not so cloddy as the exaggerated specimens now are, they were not so heavily built that their powers of locomotion were impeded..." The "powers of locomotion" of the Bulldog are not exactly helped by the wording on gait/movement in the breed standard: peculiarly heavy and constrained. Why would anyone want their dog to walk in a strangely cumbersome and unnaturally forced manner? Or is this inevitable when the standard demands forelegs wide apart, elbows which stand well away from the dog's ribs and hocks "made to approach each other", with stifles "round" (if that is physically possible). The biggest handicap to the modern non-sporting Bulldog is not so much in its unnatural movement but in its untypically short muzzle. It is significant that in those bulldog breeds developed outside Britain from stock taken there several centuries ago do not feature a muzzle-less head. The American Bulldog, the Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog, the "Olde Englishe Bulldogges" of Lolly Wilkinson in Vancouver, the 'Aussie Bulldogs' of Noel and Tina Green and the Ca de Bou or Majorcan Bulldog all have strong but balanced skulls, with appreciable muzzle length.

Faulty Breed Blueprint

The main problem met by Bulldog breeders, exhibitors and show judges in the last century or so lay in the wording of the breed standard, authorised by the Kennel Club as the design for the breed. Until recently heavily amended, this detailed description of what the breed should be like had over 250 words on the head and skull but only 30 on movement and 13 on temperament. Some of the requirements were simply a recipe for disaster: "Head massive...body short...skull large...skin upon and about head, loose and wrinkled...muzzle short...eyes well away from ears...shoulders giving appearance of being 'tacked on' body...elbows standing well away from ribs...movement - peculiarly heavy and constrained". It could have been drafted by someone who hated Bulldogs! Not surprisingly, the resultant contemporary Bulldog is an anatomical disaster. The harm has been done. These words shaped today's breed!

Distressing Consequences

As a direct result of this harmful long-lasting design specification, we have a breed of dog that is quite unlike its own ancestors, has distressing respiratory problems, cannot give birth naturally and is unable to live a normal life. Could anyone claiming affection for a breed really want its gait to be "peculiarly heavy and constrained"? I can understand fanciers wanting to perpetuate a breed as it was originally; but how can any pure-bred Bulldog breeder not only want to produce crippled dogs but dogs that are so physically different from their own forebears? It can only be explained by a selfish and unfeeling fascination with deformation. It is noteworthy that Bulldogs developed here by non-show breeders and known as Sussex, Dorset or Victorian Bulldogs do not feature the exaggerations desired by those showing in KC-sanctioned rings.

Absurd Wording

The Bulldog breed standard has historically drawn disapproval. In 1888, it was being accused, by a well-known breeder, Adcock, of being: "absurd...founded upon no basis...been foisted upon breeders...in advocating the production of a small, thin ear, he is unconsciously but certainly diminishing the thickness and volume of the skin covering the head and neck, so necessary for the protection of an essentially gladitorial animal...the tail must be destitute of rough hair, which practically means that the coat of the dog must be of an extremely fine nature...this peculiarity tends to, and has actually resulted in, diminution of the bony structures; the inferior dentition; and weakness of constitution." Certainly today's pure-bred Bulldog suffers from a number of problems created by its own approved design.

Re-creating the Real Bulldog

A number of worthy people have attempted to re-create the genuine Bulldog. Clifford Derwent, himself a successful dog breeder of other breeds, exhibitor and highly rated judge, developed what he called Regency Bulldogs. But he couldn't get the temperament right and abandoned his admirable quest. Then the late Ken Mollett of Pinner took up the challenge, with some success. Using a blend of Staffordshire Bullterrier, Bullmastiff and oversized pure-bred Bulldog, he stabilised his own distinct Victorian Bulldog type: active, agile, unexaggerated and yet unaggressive. He deserved greater support. The physical condition of our pedigree Bulldog is a matter screaming out, on humane grounds alone, for action by the Kennel Club. Yet despite their ownership of the harmfully worded breed standard, they see it as a matter for the breed clubs. But why should the latter change when their members can sell their pups for £600-£800 each? I have also seen 'Sussex Bulldogs' and 'Dorset Old Tyme Bulldogges', currently being bred by well-intentioned fanciers, that looked healthy and unexaggerated, active and agile, breathing and moving freely.

These Dorset Bulldogge fanciers are producing active athletic dogs which live long healthy lives and look real characters. The Dorset Bulldogge breeders are seeking a dog standing around 20 inches at the shoulder, ranging from 60 to 90 lbs, stocky, well-muscled, with a muzzle long enough to permit good respiration and a torso which allows natural whelping. The Sussex Club’s breeding programme is over 20 years old, and any randomly chosen Sussex Bulldog has a minimum of 12 generations behind it. They are now breeding for 20th generation dogs. The Sussex Bulldog breeders are seeking an unexaggerated dog standing around 22-24 inches at the shoulder, ranging from 105 to 120 lbs, sturdy, powerfully-developed, with a muzzle between a third and a fifth of the skull length, which should allow natural whelping.

Re-created Breed

Rumour has it that a group of continental Bulldog fanciers have approached the international kennel club, the FCI, with a request for a 'Continental Bulldog' to be recognised by them. This 'new breed' will apparently be a reversion to the old-style more athletic one, depicted in old prints and paintings, lacking the muzzle-less head, wide forefront and narrow hips of the KC-recognised breed, favoured in the show-ring here. As indicated above, an English breeder once attempted to re-create the older type, calling them Regency Bulldogs. More recently, the late Ken Mollett and his Victorian Bulldog Society members have pursued a comparable project. In Switzerland, Holland, Australia, the United States and Canada, other talented and well-intentioned breeders have produced less exaggerated specimens, with mixed success. It would be shameful surely if overseas breeders managed to produce a Bulldog, and get it registered, which more faithfully portrayed our much-loved native breed. In June 2000, I was invited to judge the Victorian Bulldog Society's 1st Annual Show at Donnisthorpe; not one of the entry there featured the needless handicaps inflicted on the KC-registered dogs.

In his Bulldogs and all about them of 1925, Barrett Fowler wrote: "...a vast number of crippled, unhealthy and grossly exaggerated specimens of the breed were being exhibited, and what is worse, winning prizes...It was the aim of some breeders to produce the most exaggerated specimens possible. They misread the Standard and taught others to misread it also."

Clearly, the pedigree breed needs a new Breed Standard; here is my attempt:

THE REAL BULLDOG – A PROPOSED BREED STANDARD

Sporting Role: To seize and hold big game (when a bigger breed) such as bison, boar and wild bulls. To bait bulls.

Working Role: To pin wayward cattle, to drive stubborn stock, to provide support for butchers and cattle farmers. To guard.

General Appearance: A powerfully-built, well-muscled, broad-mouthed but strongly-muzzled, short-haired, substantial dog, around a foot and a half at the shoulder; brindle, red or white, or fawn in colour; active, athletic, formidable-looking and hinting at great power and determination.

Characteristics: Bold, confident and protective, without unwanted aggression, naturally inquisitive, physically and mentally reliable, possessing great stamina yet able to produce bursts of dynamic energy, alert and eager to learn, devoted to its own family but suspicious of strangers, tolerant of other dogs, impressively magnanimous. Not noisy by nature.

Temperament: Mentally stable, utterly trustworthy with children, spirited at times but mainly calm and phlegmatic, showing no sign of shyness or needless apprehension, able instinctively to discern between acceptable human activity and that warranting suspicion. Can be diffident when young.

Aptitude: Willingness to investigate suspicious activity, able to track, prepared to guard without hesitation but always under control, possessing the instinct to seize and hold or 'pin' its quarry.

Construction: Must have the anatomy of an active dog, powerful but agile, strongly-made but never heavy-boned in a cumbersome way, really broad in the chest, with the ribs carried well back, strong in the neck and powerful in the head, with most of the weight on the forehand, showing appreciable width and ample length in the muzzle. A balanced dog with a low station.

Forefront: The head was designed for seizing and gripping sizeable quarry, it therefore needs: a jaw with width and length - roughly one third of the whole head length, the jaws closing in a scissor bite (slightly undershot permitted), with well-formed strong even teeth. The breed should not feature massive heads, with its accompanying whelping problems, severely undershot jaws, with its tendency to exaggerate itself with each generation, too short a muzzle, with its loss of gripping power and concomitant dentition problems, or excessive loose skin on the cheeks and foreface, flews or dewlaps; these are show ring whims not the requirements of a functional holding dog. The 'stop' is appreciable but not too deep or abrupt (associated with cleft palate). The nose is wide, displaying well-developed nostrils; the eyes are full, tight and dark. The ears are soft-leathered, high set, drop or rose, never large or hound-like. The neck is extremely powerful, strongly muscled, clean without throatiness, sweeping into the shoulders without coarseness. A low head carriage on the move is characteristic, the occipital foramen, through which the spinal cord emerges, is placed a little lower in the skull in this breed.

Forehand: The shoulder blades are set well apart; the shoulders are well laid back; the upper arm is of sufficient length to allow good forward extension; the elbows fit closely, never displaying the 'out at elbow' structure once sadly favoured in the Bulldog; the 'elbow slash' must allow a good degree of forward reach; the forelegs are straight when seen from the front but show a forward slope of pastern when seen from the side, to allow spring when jumping and landing, an important feature in a hefty active dog; without this splay feet ensue. The forelegs should be powerful but not be over-timbered, with strong flat bone preferred to round heavy bone. The length of foreleg in adult animals should roughly equal the depth of chest. The feet are round and sizeable, with strong toes, robust pads and sturdy nails.

Torso: The chest is really broad, deep and well-sprung; the body is compact and short-coupled without losing flexibility; The underline of the abdomen shows discernible but not appreciable tuck-up; the loins are wide, slightly arched and strongly muscled; the topline is level, with the length from point of shoulder to point of buttock being slightly more than the height at the withers.

Hindhand: The croup is slightly lower than the withers, falling away gently towards the root of tail. The hindquarters are extremely powerfully muscled, with well let down hocks, a distinct turn of stifle, and straight legs when seen from the rear; The feet are round, compact without being bunched, with strong tough durable pads and sturdy nails, which must not be brittle. The tail is set-on low with a thick root, carried low. A tail which is set on too high indicates too flat a placement of the croup or sacrum, so often accompanied by straight stifles and then the inevitable slipping kneecaps.

Movement: This should demonstrate obvious determination, with a strong action, powerful drive from the rear, with minimal leg lift, apparent spring and obvious economy of effort, based on good coordination of front and rear actions. The forelegs must retain separation when moving, so that the dog remains balanced. Strongly-built dogs should not 'pull' themselves along, but drive themselves along. The heavier the dog then the greater the importance of balance and sound movement, which indicates, more than any human visual judgement, sound construction.

Coat: Colour; in order of preference: red brindle, other brindle shades, solid white or white/pied, solid red, fawn or fallow. Black or black and tan is not desired.

Texture; short, close, hard, dense; softer on the head and ear leathers; the skin of the breed is thick apart from that on the head.

Size: Height at withers; 17-19" (males); 16-18" (females).

Weight; 65-80lbs (males); 55-65lbs (females). Always commensurate with height.

Faults: Disqualifying; Totally squashed nose, with no visible

muzzle.

Too straight at stifle.

Noticeably out at elbow.

Lack of 'spread' in the chest.

Cow hocks.

Wry mouth.

Visible incisors, when mouth closed.

Serious; Tiny teeth.

Thin neck.

Severely undershot.

Plaiting (front feet crossing on the

move).

Ribs not carried back far enough.

Small head (in adult animals).

Lack of drive behind.

Angle of the hock too closed.

Others; Too abrupt a 'stop'.

Poor pigmentation.

Splay feet.

Sway back.

Narrow across the hips.

Prominent eyes.

Any degree of haw.

Weak loins.

Note: Any resemblance to the Pug should be severely penalised. The pursuit of massive heads, excessive wrinkle, muzzle-less skulls and a disproportionately small pelvis is alien to the Victorian Bulldog.

N.B. This is a discussion document not the finished article. It is intended to offer a comprehensive text for future draftees.